A health care directive is any document in which you set out instructions or wishes for your medical care. Most states provide two basic documents for this purpose:

- A durable power of attorney for health care, in which you name someone you trust to oversee your health care and make medical decisions should you become unable to do so.

- A living will, in which you spell out any wishes about the types of care you do or do not wish to receive if you are unable to speak for yourself. Your doctors and the person you name as your agent in your durable power of attorney for health care must do their best to follow any instructions you leave.

Who Should Make a Health Care Directive?

Every adult can benefit from making health care directives. If you’re older or in ill health, you surely understand why these documents are important. But if you’re younger—perhaps using WillMaker to help prepare health care documents for a loved one—consider making documents for yourself now, even if you don’t think it’s necessary.

While the elderly and the seriously ill should make health care directives to smooth the way for decision making at the end of life, we tend to avoid another disturbing truth: Younger, healthy adults should also have health care directives, because an incapacitating accident or unexpected illness can occur at any time. In fact, if you look at the painful stories that make headlines, you’ll quickly notice that the bitterest family fights over end-of-life health care don’t happen when a patient is very old or has a long illness. The worst disputes arise when tragedy strikes a younger adult who never clearly expressed any wishes about medical treatment.

What Happens If You Don’t Make Health Care Directives?

If you do not prepare health care documents, state law tells your health care providers what to do. In some states, your health care providers can decide what kind of medical care you will receive. Most states, however, require them to consult your spouse or an immediate relative. The person entitled to make decisions on your behalf is usually called your “surrogate.” A few states allow a “close friend” to act as surrogate. If there is a dispute about who should be your surrogate, it might have to be resolved in court.

Whether required by law or not, if there is a question about whether surgery or some other serious procedure is authorized, health care providers will usually turn for guidance to a close relative—a spouse, parent, or child. Friends and unmarried partners, although they might be most familiar with your wishes for medical treatment, are rarely consulted or—worse still—are sometimes purposely left out of the decision-making process.

Problems arise when loved ones and family members disagree about what treatment is proper and everyone takes sides, claiming they want what is best for the patient. Battles over medical care might even end up in court, especially now that some religious organizations finance lawsuits to block the removal of feeding tubes from permanently unconscious patients. In court, a judge, who usually has little medical knowledge and no familiarity with the patient, must decide the course of treatment. Such battles—which are costly, time-consuming, and painful to those involved—are unnecessary if you have the care and foresight to prepare a formal document to express your wishes for health care.

What You Can Do With WillMaker’s Health Care Directive

With WillMaker, you can create comprehensive health care documents that are valid for your state. With these documents, you can clearly express your preferences for medical care if you become unable to communicate your wishes. Specifically, you can:

- appoint a trusted person, called your “health care agent” in most states, to oversee your medical care if you become unable to speak for yourself

- name the doctor or other health care professional you’d like to supervise your care

- specify whether you want your life prolonged with medical treatments and procedures

- identify specific medical treatments and procedures that you want provided or withheld, and

- provide instructions for donating your organs, tissues, or body after death.

You can also state any general wishes you have about your care, such as where you would like to be cared for (for example, in a particular hospice facility or at home, if possible) or any special directions that might affect your comfort or awareness (for instance, whether you would like to receive full doses of pain medication even if it makes you unaware of the presence of family and friends).

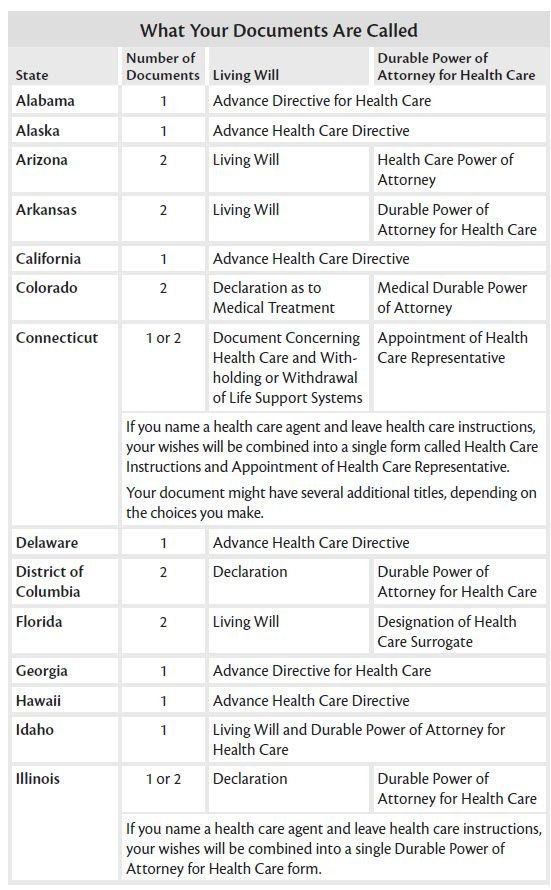

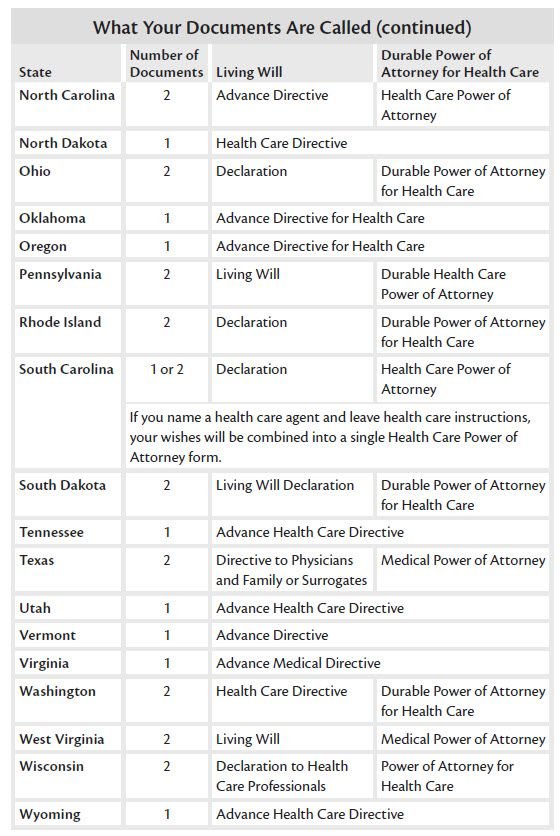

Names for Health Care Directives in Your State

The exact names of these documents vary from state to state, and some states combine the two into a single form, usually called an “advance health care directive.” The table below shows how your state handles it.

You Have the Legal Right to Direct Your Own Care

Your right to direct your own health care is well established. But that wasn’t always the case. Just a few decades ago, heart-wrenching legal battles were fought to win permission to create a document stating that life-prolonging treatments should be terminated—or continued—at the end of life.

Landmark cases involving Karen Ann Quinlan and Nancy Cruzan—two young women who became brain-damaged and unable to communicate their wishes—opened the way to laws supporting health care documents.

In the Cruzan case, decided in 1990, the U.S. Supreme Court established the constitutional right to end life-sustaining treatment if a patient’s wishes to do so are clear. The next year, the federal Patient Self-Determination Act (PSDA) took effect, requiring any facility that participates in Medicare or Medicaid to ask patients whether they have an advance directive and to inform them about their health care decision-making rights.

Now, every state has a law that permits you to express your health care wishes and requires medical personnel to follow those wishes—or transfer you to the care of someone else who will do so.

Hospitals Might Have Their Own Rules

For example, Catholic hospitals and care facilities might require that all patients receive artificially administered food and water at the end of life, even if a patient has a valid health care directive saying that’s not what the patient wants. In these facilities, patients will have to accept treatment or be transferred to another facility that will respect their wishes.

It might be worthwhile to familiarize yourself with the policies of the facilities you are likely to use. That way, you and your health care representative will know where to go for care in an emergency. And if you’re making plans for long-term care, you can do so with your eyes open to the rules of your treatment providers.