After you've done the hard work of putting together a durable power of attorney, you must carry out some simple tasks to make sure the document is legally valid and will be accepted by the people with whom your attorney-in-fact may have to deal. This section explains what to do.

- Before You Sign

- Signing and Notarizing

- Witnessing

- Obtaining the Attorney-in-Fact's Signature

- Preparation Statement

- Recording

Before You Sign

Before you finalize your power of attorney, you may want to show it to the banks, brokers, insurers and other financial institutions you expect your attorney-in-fact to deal with on your behalf.

Discussing your plans with people at these institutions before it is final—and giving them a copy of the durable power of attorney, after you sign it, if you wish—can make your attorney-in-fact's job easier. An institution may require that you include specific language in your durable power of attorney, authorizing the attorney-in-fact to do certain things on your behalf. You may have to go along if you want cooperation later. If you don't want to change your durable power of attorney, find another bank that will accept the document as it is.

Signing and Notarizing

A durable power of attorney is a serious document, and to make it effective you must observe certain formalities when you sign the document.

In almost all states, you must sign your durable power of attorney in the presence of a notary public. (In just a few states, you can choose to have your document witnessed or notarized. See "For California, Indiana, Michigan, or Washington Residents: Making the Choice," below.) In many states, law requires notarization to make the durable power of attorney valid. But even where law doesn't require it, custom usually does. A durable power of attorney that isn't notarized may not be accepted by people with whom your agent tries to deal.

The notary public watches you sign the durable power of attorney and then signs it, too, and stamps it with an official seal. The notary will want proof of your identity, such as a driver's license that bears your photo and signature. The notary's fee is usually inexpensive—less than $20 in most places.

Finding a notary public shouldn't be a problem; many advertise online or in the yellow pages. Or check with your bank, which may provide notarizations as a service to customers. Mailbox stores, real estate offices, and title companies may also have notaries.

If needed, you may be able to find a notary who will come to your home or hospital room, and in some states, you may be able to have your document notarized on a video call. To find out what is possible in your area, call a few local notaries and ask what services they provide. Expect to pay a reasonable extra fee for mobile and remote notary services.

Witnessing

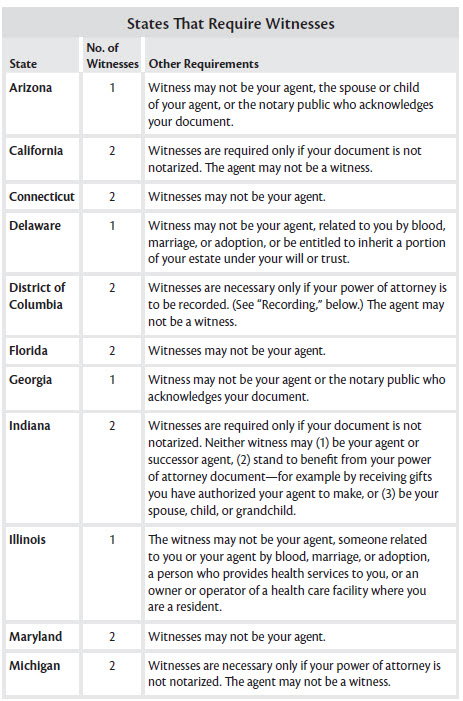

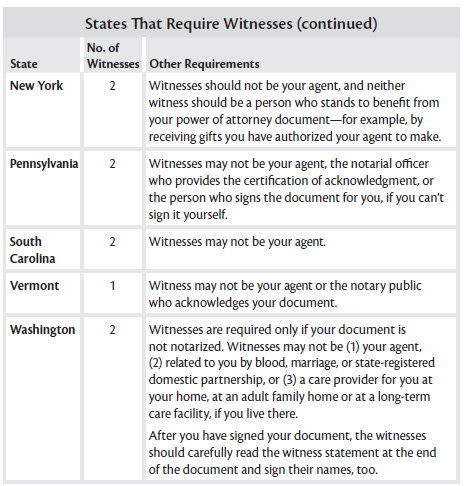

Most states don't require the durable power of attorney to be signed in front of witnesses. (See "States That Require Witnesses," below.) Nevertheless, it doesn't hurt to have a witness or two watch you sign, and sign the document themselves. Witnesses' signatures may make the power of attorney more acceptable to lawyers, banks, insurance companies, and other entities the agent may have to deal with. Part of the reason is probably that some other legal documents with which people are more familiar—including wills and some health care directives—must be witnessed to be legally valid.

Witnesses can serve another function, too. If you're worried that someone may challenge your capacity to execute a valid durable power of attorney later, it's prudent to have witnesses. If necessary, they can testify that in their judgment, you knew what you were doing when you signed the document.

The witnesses must be present when you sign the document in front of the notary. Witnesses must be mentally competent adults, preferably ones who live nearby and will be easily available if necessary. The person who will serve as agent should not be a witness. In some states, the agent must sign the durable power of attorney document. (These states are listed below.)

Your notary public should not also be a witness. If you must also have your power of attorney witnessed, the notary should not serve as a witness, even if your state does not explicitly prohibit it. Find separate individuals to witness and notarize your document.

If you live in California, Michigan, South Dakota, or Washington, your durable power of attorney is valid if you have it notarized or if you sign it in front of two witnesses. Some people feel most comfortable using both methods together, but you are legally required to choose only one. In these states, you will be prompted to indicate how you want to finalize your document.

When choosing a method, there's one important consideration to keep in mind. If your power of attorney grants your attorney-in-fact authority over your real estate, you should absolutely have your document notarized. This is because you will have to put a copy of your document on file in the county recorder's office (see "Recording," below)—and in order to record your document, it must be notarized.

(Cal. Prob. Code § 4121, M.C.L.A. 700.5501, SDCL § 59-7-2.1, RCW 11.125.050.)

Obtaining the Attorney-in-Fact's Signature

In the vast majority of states, the attorney-in-fact does not have to agree in writing to accept the job of handling your finances. The exceptions to this rule are California, Delaware, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania and Vermont. In these states, the attorneys-in-fact (and alternates) do not need to sign the document unless or until they need to use it.

California

In California, your attorney-in-fact must date and sign the durable power of attorney before taking action under the document. Ask the attorney-in-fact to read the Notice to Person Accepting the Appointment as Attorney-in-Fact at the beginning of the form. If your attorney-in-fact will begin using the power of attorney right away, he or she should date and sign the designated blanks at the end of the notice. If you've asked your attorney-in-fact not to use the document unless or until you become incapacitated, there's no need to obtain the signature now. Your attorney-in-fact can sign later, if it's ever necessary. (Cal. Prob. Code § 4128.)

Delaware, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire and Pennsylvania

In Delaware, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire and Pennsylvania, your attorney-in-fact must complete and sign an acknowledgment form. (Delaware calls it a certification.) This simple form ensures that your attorney-in-fact understands the legal responsibilities involved in acting on your behalf. When you print out your durable power of attorney, it will be accompanied by an acknowledgment form for your attorney-in-fact to sign.

If your attorney-in-fact will begin using the power of attorney right away, give the acknowledgment form to him or her along with the finalized, original power of attorney document. Your attorney-in-fact must complete the form and attach it to the power of attorney before taking action under the document.

If you've asked your attorney-in-fact not to use the power of attorney unless or until you become incapacitated, keep the acknowledgment form together with the original power of attorney document. Your attorney-in-fact can complete it later, if it ever becomes necessary to use the power of attorney. (Del. Code Ann. tit. 12, § 49A-105, Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 700.5501, Minn. Stat. Ann. § 523.23, N.H. Laws § 564-E:113, 20 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann. § 5601.)

New York and Vermont

If you live in New York or Vermont, your attorney-in-fact must sign the power of attorney before taking action under the document. If your attorney-in-fact will begin using the power of attorney right away, ask him or her to print and then sign his or her full name in the designated blanks at the end of the form. (In New York the agent must also have this signature notarized.) If you've asked your attorney-in-fact not to use the document unless or until you become incapacitated, there's no need to obtain the attorney-in-fact's signature now. He or she can sign the document later, if it's ever necessary. (N.Y. Gen. Oblig. Law § 5-1513, Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 14, § 3503.)

Preparation Statement

At the end of the power of attorney interview, you will be asked to enter the name and address of the person who is preparing the power of attorney. This information is used to add a "preparation statement" to the end of your power of attorney document. Some states or counties require a preparation statement to record a document. But even where the law doesn't require it, tradition (or a county recorder's habit) often does, so Nolo's Durable Power of Attorney for Finances includes a preparation statement on every durable power of attorney for finances.

The preparation statement is a simple listing of the name and address of the person who prepared the document. In most cases, the name of the principal and the name of the person who prepared the document will be the same: your own. Occasionally, however, someone may prepare a form for another person—an ailing relative, for example. In that case, use the name and address of the person who stepped in to help.

Recording

You may need to put a copy of your durable power of attorney on file in the land records office of the counties where you own real estate, called the county recorder's or land registry office in most states. This is called "recording," or "registering" in some states.

Only South Carolina requires you to record a power of attorney for it to be durable—that is, for it to remain in effect if you become incapacitated. (S.C. Code Ann. § 62-8-109.)

In other states, you must record the power of attorney only if it gives your attorney-in-fact authority over your real estate. Essentially, this means you must record the document if you granted the real estate power. If the document isn't recorded, your attorney-in-fact won't be able to sell, mortgage or transfer your real estate.

Recording makes it clear to all interested parties that the attorney-in-fact has power over the property. County land records are checked whenever real estate changes hands or is mortgaged; if your attorney-in-fact attempts to sell or mortgage your real estate, there must be something in the records that proves he or she has authority to do so.

There is no time limit on when you must record a durable power of attorney. So if you've created a document that won't be used unless and until you become incapacitated, you may not want to record it immediately. Your attorney-in-fact can always record the document later, if he or she ever needs to use it.

Even if recording is not legally required, you can do so anyway; officials in some financial institutions may be reassured later on by seeing that you took that step.

Where to Record

In most states, each county has its own office for a recorder or registry of deeds. If you're recording to give the attorney-in-fact authority over real estate, take the durable power of attorney to the office in the county where the real estate is located. If you want your attorney-in-fact to have authority over more than one parcel of real estate, record the power of attorney in each county where you own property. If you're recording for any other reason, take the document to the office in the county where you live.

How to Record

Recording a document shouldn't be complicated, though some counties can be quite fussy about their rules. (See below.) You may even be able to record your document by mail, but it's safer to go in person. Typically, the clerk makes a copy of your document for the public records and assigns it a reference number. In most places, it costs less than $10 per page to record a document.

Check Your County's Requirements

Check your county's recording procedures before you finalize your document. Some counties will ask you to meet very particular requirements before they will put your power of attorney on file. Or, if you don't adhere to their rules, they will charge you an extra fee for filing the document.

For example, in some counties, you may be required to file an original document, rather than a photocopy, with the land records office. In this case, you'll need to make a second original, being sure to have it signed, notarized and witnessed (if necessary), just like the first.

And some counties require a margin of a certain number of inches at the top of the first page of a power of attorney. This is where they put the filing stamp when you record the document. Local customs vary widely here; some counties will accept a standard one-inch margin while others ask for a margin of two, three or even four inches.

To avoid hassles and extra expenses, you should call the land records office before you finalize your power of attorney to make sure you're prepared to meet any special requirements for putting it on file.